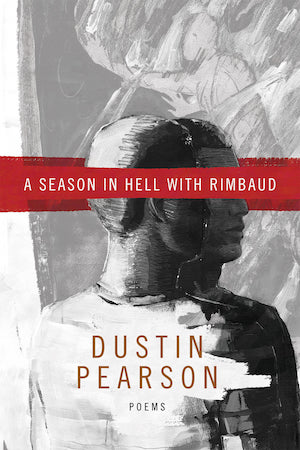

A Season in Hell with Rimbaud

About the book

In pursuit of his brother, a man traverses the fantastical and grotesque landscape of Hell, pondering their now fractured relationship.

The poems in Dustin Pearson’s A Season in Hell with Rimbaud form an allegorical travelogue that chronicles two brothers’ mutual descent into hell. When the older brother runs off by himself, the younger brother begins roaming Hell’s different landscapes in search of him. As he searches, the younger brother ruminates on their now fractured relationship: what brought them here? Can they find each other? Will their bonds ever be repaired?

In the tradition of Virgil, Dante, Milton, Swift, Shelley, Joyce, Sarte, and especially Arthur Rimbaud, Pearson leads his speakers on a speculative, epistolary journey through the nether realm inspired by Christian beliefs and tradition. Drawing on the works of French Symbolists and the literary traditions of the American South, A Season in Hell with Rimbaud guides readers through an intimate rendering of one brother’s journey to find his lost and estranged brother, perhaps recovering a part of himself in the process.

You can lose your brother to Hell/ and still be happy inside your house,’ begins one of Pearson’s striking and unforgettable poems. Pearson is at once metaphysical and allegorical. While summoning Rimbaud’s symbolism poetics, he creates a voice uniquely his own, with questions of brotherhood, performative masculinity, and the horrors and vulnerabilities of our mortal bodies. There are many rooms to open in each of Pearson’s poems. A Season In Hell With Rimbaud is a rich and thorough collection. Each time the speaker’s brother is addressed, a history of violence and traumas that the brother has been subjected to in Hell is simultaneously summoned. But is hell another dimension, an internal space, an external space, or is it right here on earth? Pearson keeps reminding us that, ‘The house has many rooms,’ and we find meaning inside and out of each real, imagined and metaphysical space. What a poetic accomplishment this is!

– Raymond Antrobus, author of All the Names Given

Throughout this infernal journal, I couldn’t help but to think of Hélène Cixous’s Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, of her lecture “The School of Dreams,” of its passages between Mendelstam’s wondering “how many pairs of shoes Dante must have worn out in order to write The Divine Comedy,” and Cixous’s proposition that writing is, mostly, “not arriving.” Somewhere in the middle, Rimbaud “has apparently been walking for centuries,” and Cixous declares the walking body responsible for the enfleshment of our dream worlds.

All the walking in Dustin Pearson’s oneiric Season in Hell is carnal / etymologically carnival in this way. The flesh putrefies and bubbles. From cuts in the feet the blood leaks and puddles and muddles. Skin-splitting is a critical function of discovery. The hellscape lives, roils, and revolts per its noxious nature, and as the speaker threads it in search of their brother (in pursuit of themself), Hell gets inside you, becomes the body and what can happen to it, and remains strange: Pearson is a still foreigner there, a traveler who does not arrive. Lately, as I gain familiarity with the cinema of “body horror,” I give thanks for the intimacy of gore and what possible agape arises in the rend(er)ing of our simplest vulnerabilities. I likewise give thanks for Pearson’s dream-walking poems with titles like hardcore band names, for how they mirror the interior wherein I am a fallible brother, a friend in the distance, a companion simultaneously corruptible and committed.

– Justin Phillip Reed, author of The Malevolent Volume

If, as Rimbaud tells us, believing you’re in Hell means you’re there, A Season in Hell with Rimbaud is Dustin Pearson’s Dantean descent. No Virgil, no Beatrice, but a brother—one who could ‘clap a boulder to dust,’ whose presence augured the world: ‘There wasn’t a time/ I didn’t have/ a brother. When/ my eyes opened,/ he was already here.’ It’s an epic story, braiding planes of mind and spirit, reaching across time and space to distant cosmologies, poetries, theologies. But it’s also decidedly granular—sheets pulled up over a headboard, geysers, a red balloon. Pearson has written an unforgettable story of two brothers and the myriad universes roiling between them: ‘If the only world is a Hell with my brother / in it, being with him will make a new one.

– Kaveh Akbar, author of Pilgrim Bell